Advocating for an offbeat hobby

If you ever needed a rosy vision of the apocalypse, I recommend seeking out a used bookshop. Not just a shop that sells used books, but a bookshop that itself has been used: worn, lived-in, exploited.

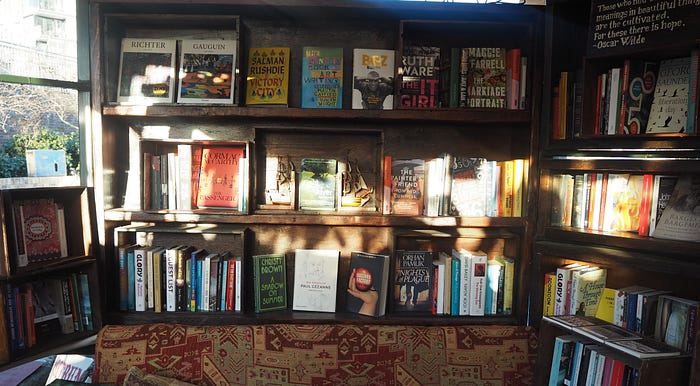

The atmosphere is unbeatable. Expect an ambience of apprehensive shuffling and dry coughs dampened by walls of paperbacks. Dustiness and decay. A barricade of orange Penguin classics mass-produced after WW2. The appearance of a few scavenging surveyors and the dishevelled worker who probably lives there, sustaining themselves on little more than the collected poems of Bashō and Sylvia Plath.

Bookshops don’t so much sell products, as ideas — like cash, the material books are printed on is worth little, the value is in what they represent. In second-hand bookshops, it’s as if the ideas have traded hands, been left to ferment and ultimately abandoned, before going up for adoption. Each purchase is a contract and a commitment.

I will admit buying books is not always a rational process. Treasure hunting comes to mind — it’s spontaneous, chaotic and deeply involving. Strolling into a pristinely arranged chain is not the same. You never know what you will find in the realm of the preowned. A copy of The Outsider that has been left outside. A well-travelled Homer’s Odyssey. A War and Peace that has actually been read.

Committing to this habit in all its fanaticism has drawn me into new literary territories. I’ve also gained an appreciation for independent booksellers and their obsessive, hermit-like occupations.

However, when I’m not satiating my own novel goblin I sometimes reflect on the impact of my actions. Is buying second-hand harmful for an industry that ultimately relies on the bottom line?

Buying through the backdoor

The controversial side of second-hand books is that neither the author nor publisher directly benefits from their sale. It’s easier to justify buying classics or dead authors this way, since only their estate is missing out. Living authors — with their need to consume genuine food, and not just the crumpled paper of first drafts — clearly have more to lose.

While I think it’s important to purchase new releases, I will also defend the used market. A second-hand sale is often not equivalent to a lost retail purchase. Used bookshops are closer to libraries than black markets: they lead to the discovery of authors, generate interest and ultimately convert to fresh sales.

I also think it’s a mistake to assume that specialist book retailers, like the UK’s Waterstones, are comprehensive. They are selling books that they consider to be relevant, but this rarely covers all bases. For classics, or renowned books, we are seeing the latest reissue, but these are not necessarily definitive.

For example, look at translations of foreign language classics — say, Flaubert. Each edition of Madame Bovary (there are many) is essentially a reinterpretation by its translator, shaped by the era and environment they were translated in. The older a text, the greater the level of interpretation being applied.

Even earlier versions of contemporary novels are worth salvaging for posterity’s sake. The recent outrage over Roald Dahl’s re-edited catalogue is an extreme example, but a reminder that bowdlerizing beloved books is never off the table for publishers as long as there is a drive to reach new audiences.

One of the charming things about older editions is that, from their covers to their blurbs, the quality of the paper, and the formatting of the text, they are artifacts; statements of intent of their time. Yes, I believe great works of literature can be timeless — that doesn’t mean we should devalue or detract from the context that formed them, nor how they were originally marketed.

Of course specialist retailers are the main source of income for modern authors, outside of online sales. However, schemes like AuthorSHARE are addressing this issue by compensating authors for second-hand sales. As more independent retailers adopt this approach, hopefully there will be a healthier relationship between authors and the used book market.

If there’s a black sheep in the industry, it’s Amazon. While the corporation has modernised how we access literature, its killing off of the high street is a continual threat to brick-and-mortar bookshops, particularly independent shops. These are both a vital outlet for the authors and refuge from the rampant consumerism that has increasingly come to define urban spaces.

Quiet, please

If you have ever felt the warmness of stumbling upon a vinyl bin, a second-hand instrument shop, a hole-in-wall café or even a small, dilapidated church then you can appreciate the need for spaces that are impractical and outdated, yet human.

This is how I see second-hand bookshops. They are temples of stories and ideas, hovels of the obscure and antiquated, Alexandrian libraries compressed into sometimes absurdly tight spaces.

London has its fair share. From Bloomsbury’s iconic Judd Books and the radical basement Skoob books, Hampstead’s crypt-like Keith Fawkes and innovative pop-ups, like the bookbarge Word on the Water hanging out in Coal Drop Yard, the city is rife with literary havens. If you want rare first editions check out the basement in Waterstones Gower Street — proof that large chains can still offer something unique.

But if there’s a special energy to these spaces it’s not just in the environments themselves. It’s from people who are occupying them, mutually curious snoopers, wordlessly engaged in an archaic ritual. It might seem banal, but I warn you — it can become a compulsion.

My favourite finds

- Kōbō Abe (安部 公房) — The Ruined Map

2. Flann O’Brien — At Swim-Two-Birds

3. Albert Camus — The Outsider

4. Ursula Le Guin — The Dispossessed

5. Fyodor Dostoevsky — The Idiot

6. Rabelais — Garantua and Pantagruel

7. Jean-Paul Sartre — Le Mots

8. Tom McCarthy — Remainder

9. Salman Rushdie — Midnight’s Children

10. Anonymous — Sir Gawain and the Green Knight